- Home

- Robin Denniston

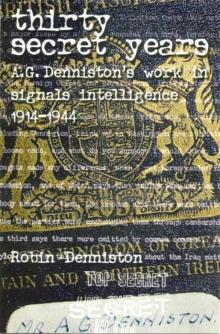

Thirty Secret Years

Thirty Secret Years Read online

Thirty Secret Years

A. G. Denniston’s work in signals intelligence 1914 – 1944

Robin Denniston

To

Margaret Finch

and

Libby Buchanan

with love

When GC&CS moved out to Bletchley Park at the outbreak of war in September 1939 one observes that the founding fathers of BP – Commander Alastair Denniston, Nigel de Grey, Dilwyn Knox and others – had all learned their trade in the Room 40 … another war kept their hand in at GC&CS through two decades of peace. The tradition of the British is tradition.

Ronald Lewin, Ultra Goes to War

The transatlantic alliance forged at Bletchley Park was just as important as the codebreakers’ effect on the war.

Michael Smith, Station X

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Acknowledgments

Preface

Chapter 1 A. G. Denniston 1881 – 1941

Chapter 2 Room 40: 1914–15

Chapter 3 Scapa Flow 1919

Chapter 4 His Secret Years: Strengths and Weaknesses

Chapter 5 Diplomatic Eavesdropping 1922–44

Chapter 6 The Government Code and Cypher School between the Wars

Chapter 7 How News was brought from Warsaw at the end of July 1939

Chapter 8 Report on Berkeley Street crypto activities in 1943

Chapter 9 AGD’s views on US/UK crypto co-operation

Chapter 10 How the story broke

Postscript

List of Abbreviations

Bibliography and Sources

Plates

By the Same Author

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to Candida Connolly for starting me off, and to Ralph Erskine and Mavis Batey for encouragement and valuable information.

Preface

My father’s death in Lymington cottage hospital in 1961 at the age of 79 was marked by no obituaries anywhere. He had been in charge of the Government Code and Cipher School from 1919 to 1942: firstly at the Admiralty where he had since 1914 been a long-serving watch-keeper at Room 40 OB (Old Buildings), whose staff spent their wartime years decrypting, translating, assessing and distributing secretly intercepted messages between the German High Command and the Grand Fleet. For this work he was made an officer of the newly created Order of the British Empire and entrusted by Lloyd George’s postwar cabinet with the transformation of Room 40 into the Government Code and Cipher School - by 1941 rechristened Government Communication Headquarters. The new team of some 40 people, increased to 60 by 1939 successfully deciphered the diplomatic traffic of Italy, Spain, France, Turkey, several South American republics and Saudi Arabia.

This remained officially non-existent except for a yearly sum set aside for it in the Foreign Office budget. Resources were scarce as the Geddes axe nearly threw out (to mix metaphors) the baby with the bathwater. Nonetheless the product of GC&CS, assessed with care by my father and his helpers, was regularly circulated to a score of government departments and named individuals.

Churchill, by then out of office, had himself set up Room 40 in 1914, still managed to see interesting intercepts through Major Desmond Morton, a friend of his with contacts in the right places.

The interwar years saw a major crisis when the new Soviet leadership’s traffic was intercepted and its cipher broken, thanks to Ernst Fetterlein, a Kremlin apparatchik who fled the country after the Revolution and settled in London, commuting daily to Whitehall, where the discoveries of GC&CS were revealed in Parliament, much to my father’s disgust, as the new Soviet diplomats reverted to unbreakable one-time-pads. Later, Italian aggression in Abyssinia created a new source of relevant messages and the Italian section in Whitehall was reinforced by art history scholars of the Renaissance.

The great achievement of the interwar years began in July 1939 when my father and a colleague, A. D. Knox, crossed Germany by train and entered Poland to meet their French and Polish counterparts at Pyry near Warsaw. The two middle-aged secret agents - Denniston and Knox - returned through Germany, crossed the channel and, back in Whitehall, produced a German Enigma machine encipherer the Poles had given them. A fortnight later WW2 started and the department moved to Bletchley Park (see chapter 7).

The rest is indeed history. Why, then, did not The Times and the Guardian publish any reference to my father’s life and death in 1961? I have spent time since then trying to find out. By 2001 his lifework had been scrutinised by leading historians of secret intelligence, and his entry in the new Oxford DNB by Ralph Erskine is a true and lasting tribute to this silent and enigmatic figure.

Following his retirement on 1 May 1945 on an annual pension of £591, my father took, briefly, to schoolmastering but found the going too hard, so he and my mother retired in the New Forest. Later, in 1958, my mother died of breast cancer, so my father went to New Milton where my sister Margaret lived with her family after she married the vicar there, Geoffrey Finch. She looked after the frail and distraught father she loved until his death two years later. It is to her memory that I dedicate this short book. I also dedicate it to his favourite niece and god-daughter who wrote this as the book was going to press:

Alastair Denniston was not only my favourite uncle but also a very special Godfather. How lucky I was that my Mother, always deeply proud of her brother, asked him to undertake this extra duty! It made us especially close.

This special warm relationship began when I was shipped off to school in Kent at the age of 13. At the beginning of each term he would meet a very fearful child off the train from Leeds at Kings X and take me quietly across London to the ‘school train’ at Charing Cross. In spite of the heavy burden he must have been carrying at this time - 1936-38 - he appeared to me to have all the time in the world for a very nervous homesick youngster, chatting warmly about his very special sister (my mother) and all our family ‘doings’, and telling me of the holiday escapades of his beloved son and daughter - my cousins Robin and Y.

I remember once he told me that he had decided to swap birthdays with his son Robin, who was born on Christmas Day. He and his wife had decided that a small boy should not have to cope with birthday and Christmas on the same day so that was why Robin should always celebrate his birthday on December 1st. He would be very happy to have his on Christmas Day, and so it was until Robin was grown up.

Holiday times often brought the two families together, either with us up in Yorkshire or in the South. I was invited down to their cottage at Barton-on-Sea. Uncle Alastair met me again in London and the drive down was yet another chance to get to know each other. He said to my mother after the trip that getting me past Walls Ice Cream ‘Stop Me and Buy One’ bicycles was like getting a dog past lamp posts! I remember that the sun always shone at Barton.

Perhaps one of the happiest and most recent memories of Uncle Alastair was well after the war when he would come to Yorkshire to stay with my parents in Upper Nidderdale. My father had a grouse moor and shooting days were full of expectation and excitement. Beaters sent out to drive the birds forward were an integral part of the organisation. Uncle Alastair - with no wish to use a gun -lined himself up with the beaters with his white flag and stumped across the heather. Everyone loved him and you could hear the other beaters call “Come on Uncle Alastair” or “Are you alright there, Uncle Alastair?” Everyone really enjoyed his company, not remembering that he had won the war for us, but because he was such a genuine quiet loveable person.

Beside my bed, in its original red and black Swan pen box, I always keep his silver pencil which his children gave me, accompanied by a letter written to me in Canada for Christmas

1960, signed, as ever, ‘your affectionate Godfather’.

The letter from my father she refers to was written six week before his death and is reproduced in part overleaf to show how strong his handwriting remained.

Robin Denniston October 2006

Part of the letter written by Alistair Denniston to his niece and god-daughter, Elizabeth Currer-Briggs, in December 1960 shortly before his death.

CHAPTER ONE

A. G. Denniston 1881 – 1941

I

My father was born on 1 December 1881, the eldest of three children. Their parents, my grandparents, had met in the early 1870s, and married when my grandfather, then a 23-year-old doctor who failed to get a post in Edinburgh where he graduated, took employment with the Stafford House Mission. This sent doctors, nurses and supplies to war stricken Turkey, and in 1878 Dr James Denniston found himself in charge of a large hospital in Erzurum, tending the Turkish soldiery dying daily from wounds, dysentery and frostbite in the inhospitable climate of the Eastern Anatolian plateau, attacked by their aggressive northern neighbours and ancestral enemies, the Russians. Dr Denniston’s skilled work as a surgeon was highly rated by Turkey. He also wrote back to his fiancée describing vividly the plight of the young Turkish conscripts who suffered and died despite his ministrations and those of his colleagues. His fiancée was Agnes Guthrie whom I remember in the 1930s as a little old lady (barely 5ft) in quiet retirement in a Kensington nursing home, visited daily by her elder son, my father.

Back from Turkey Dr James took a job as GP in the wet and windy Argyll seaside resort of Dunoon where his children were brought up and schooled. This is not a book about him, but it is recorded how kind and skilled he was at tending the illnesses of his patients, mainly poor, who would reward him with a chicken if they could not pay fees. He started the cottage hospital in Dunoon, and his name and work is still respected there, in the records. He did not return from Turkey unscathed, for he contracted TB as a result of his work amongst the dying Turkish soldiery. When his children were very young the family moved south, to Cheshire, where it was thought the climate would be better for his condition. It was not. He was advised to make sea voyages, in the belief that the sea air would cleanse his lungs. It did not. He travelled as ship’s doctor across the world, at one stage taking his wife and infant daughter, Biddy. He died when my father was 11.

Alastair Denniston, like his younger brother Bill and sister Biddy, was clever and resourceful. He kept many of the prizes won at Bowdon College. He did not go to a British university but to French and German ones – the Sorbonne and Bonn University.

These are hidden years. There are no letters. Perhaps there are records in Paris. Where did he stay? Was it a lonely life? Who helped him? We shall never know. He certainly became a trilingualist, able to compile a German grammar much used in British schools. He spoke and wrote French fluently, as did most Foreign Office officials.

He was a bright, resourceful young Scotsman with little behind him. He was also a brilliant athlete, playing hockey for Scotland in the 1908 Olympics. He played games when he became a language teacher at Merchiston Castle, Edinburgh and later at the Royal Naval College at Osborne in the Isle of Wight. He continued to play until his retirement in 1945.

In late 1914 he was called up to the Admiralty at the start of World War One, because of his German expertise. German naval wireless messages were being intercepted and their Lordships realised that if they could be decoded, translated and distributed within naval circles they might help the war effort against Germany. So he joined Room 40 OB in the Foreign Office, staying on till 1919 and later becoming head of the interwar bureau called the Government Code and Cipher School, which took over the wartime work of Room 40 OB. GC&CS flourished and succeeded, in absolute secrecy, in reading diplomatic intercepts from all the major nations recovering from the war, becoming, by 1938, the fledgling GCHQ which is still with us.

By his own efforts he remained head of GC&CS until 1942 when he returned to London from Bletchley Park and supplied the British Government with the diplomatic intercepts which kept the recipients in daily touch with the strategic thinking of friends, enemies, and particularly neutrals. That was his life work and his great achievement.

* * *

II

1941 was a terrible year for the Allied war effort. But when on 7 December the Japanese destroyed many of the US’s finest ships at Pearl Harbor, relief was felt by all with privileged access to the daily progress of the war, and by none more than my father.

From 1940 he shared with the Prime Minister, the service ministries, the British commanders-in-chief and a few close colleagues at Bletchley Park where he worked, daily access to the intercepted, decrypted, and translated messages of the German Air Force (since early 1940) the Abwehr and the commanders of the U-boat offensive in the North Atlantic. He also monitored and distributed the diplomatic and commercial decrypts of all the major neutral powers like the USA, Turkey, Siam, and much valuable information from two of the three Axis powers, Italy and Japan.

It was within a day or two of Pearl Harbor that his colleague since 1916, Dilwyn Knox, with a few lady assistants of intelligence and discretion, broke into the German Police/Abwehr/Gestapo Enigma. It was another of my father’s secret colleague over 25 years, Nigel de Grey, who mastered the implications of the Gestapo reports of the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Jews in Eastern Europe, at a time when the USA and the USSR were still undecided whether or not to stay neutral in the European fracas, soon to become WW2.

In January Britain faced a bleak future. The invasion scare was still on. Her allies were few and far between – Canada, Greece, Australia, South Africa, India, New Zealand – while the enemy had conquered the whole of Eastern Europe from the Baltic to the Black Sea and were flushed with victory. We were not downhearted, but it’s difficult with hindsight to see why we were not terrified out of our wits.

In the fourteen months that followed, many things went from bad to worse; but two important events, closely charted by Bletchley Park, assured those in the know that Hitler could not win. The first was when, after the early months of 1941, he expanded the Greater Reich – already in Jugoslavia and Bulgaria – into the Ukraine, Byelorussia (now Belarus) and to the gates of Leningrad and Moscow. Hitler had turned against his real enemy, the Soviet Union, and brought Stalin in on the Allied side on 22 June. The German eastward advance of the autumn against well prepared, brave and effective opposition from Soviet armour and soldiery, seemed and nearly was unbeatable. It stopped only at the gates of Moscow after the most gruelling and devastating land battles in history.

The second was in the Far East, where Japan’s hostile intentions against British imperial interests had been followed as assiduously as those of the Axis powers by Bletchley Park. By the autumn indications were clear with those who understood the import of the diplomatic and naval ‘messages’ intercepted, decrypted and circulated by the Japanese section there, that the war would spread, and Japanese imperial aggression finally ensured American participation on the Allied side. That was what Churchill had worked for so unremittingly. It was this that saved Britain from invasion and ultimately ensured victory.

But before that and despite the successful British campaign in North Africa against the Italians and later Germany, our losses in the battle of the Atlantic brought us almost to our knees. Tonnages lost in those 14 months all but crippled the British war effort. Later in the year Japanese successes in the Far East produced yet another spectre of gloom, defeat and disgrace. The southward campaign which brought Hongkong under Japanese hegemony on Christmas Day 1941 was followed by the fall of Singapore in February 1942. Sir Alexander Cadogan, FO chief who had already been through so much, told his diary, ‘This was the darkest day of the war’.

So 1941, though a horrendous year of crisis, new enemies, revelations of our own strategic and naval weaknesses against the might of the German Wehrmacht, saw also two events which eventually made victory certain – Germa

ny’s declaration of war against the Soviet Union in June and Japan’s declaration against the USA, following Pearl Harbor on 8 December.

* * *

III

Churchill called in at Bletchley Park on January 31, 1941, to see the codebreakers at work. Under conditions of maximum security 2,000 specialists were now staffing this extraordinary institution and enjoying dramatic successes despite shortages of clerical labour and equipment. He must also have called at Lavendon Manor, where the Diplomatic Section was working on American, Hebrew, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Vichy French, German, Japanese and other diplomatic ciphers, because Cadogan’s diary refers to WSC and Eden both happening to see an intercept which makes it look as though we might get the Germans out of Afghanistan. One section was even working on American cipher messages, and Commander Alastair Denniston, their chief, would recommend that (‘in view of ultimate peace negotiations’) they keep abreast of Washington’s code changes, despite the currently superficially ‘intimate’ relations.

In February 1941 Bletchley Park was growing too fast for its existing management structure. The service ministries, in particular the War Office, found its anarchic, apparently chaotic and haphazard management unacceptable. The generals and colonels well knew the value of BP’s product but felt administration should be in more professional hands. When it was discovered that two key positions – of chief billeting officer and of ‘auntie’ to the dozens of young female secretaries, cryptographers and service people – had both been filled by my father with his personal friends, it was inevitably assumed that he was out of his depth. Yet those two appointments actually turned out well. The billeting officer was Leslie Reid, our next door neighbour when we lived in Chelsea in the early 1930s; and the aunt-figure was the wife of the deputy head of MI6 reporting to ‘C’, Valentine Vivian. Both were able, experienced, efficient, committed and discrete managers; neither had any qualifications. It was to be over a year before the great change was made which resulted in his removal from Bletchley Park. And his hand on the tiller at Bletchley became more spasmodic in the first half of the year as a result of two things – his increasing ill health and his two visits to North America to build the USA-Canada three-way liaison with Bletchley – the success of which crowned his secret career and eventually brought his achievement into the history books.

Thirty Secret Years

Thirty Secret Years