- Home

- Robin Denniston

Thirty Secret Years Page 2

Thirty Secret Years Read online

Page 2

On 27 February he was diagnosed in Harley Street with a stone in the bladder. Only two days later he was entertaining a trio of the top American cryptanalysts to lunch at the start of the close signals intelligence Anglo-American relationship, now documented in the archives of both allies.

Bletchley Park was of course in hourly touch both with the French cryptographic effort, evacuated and exiled as Vichy France took over the whole country, while the great Polish founders of the Enigma attack, barely escaping with their lives via Romania, France and Spain, fled from country to country until they reached England where they were left to low level interception at the Polish HQ at Boxmoor, Surrey.

So the productivity of Bletchley throughout 1941 contrasted with its chaotic management. In April AGD asked ‘C’ to ask Lord Hankey to recruit more mathematicians for BP. By June he had been away for two months without delegating full responsibility to his second-in-command. Lacking a leader, quarrels broke out. The service ministries never liked civilian control of their personnel or the product they had come increasingly to value. In C they found an unhelpful opponent. Yet he had little grasp of what was going on at Bletchley and confidence between him and my father was not strong. No contact between them appears in the released documents of the period. No-one knew how long my father’s ill health would last, or whether and when he would return to full-time duty with facilities unimpaired.

Meanwhile, minutes of June management meetings show BP accused of sabotaging interservice co-operation; Birch became overlord of both Italian and German naval sections; Cooper called for more resources for his (air) section. BP was in direct touch with French crypto (Bertrand) and also supplying machines to the Finns. Also cipher breaking was increasing at the Middle East HQ. BP tasked eight Polish signals experts stationed at Stanmore to cover Soviet Air Force communications.

Security and adequate accommodation for new staff were constant headaches for the interim management. In July the diplomatic section was relocated from Elmer’s school to BP. More Vichy and Free French ciphers were becoming available to BP. Travis reprimanded Saunders for going over his head about building needs for the expanding Hut 3, and threatened him with instant dismissal. BP’s relations with RSS ‘Radio Security Service’ caused concern, and a bright spark from RSS, Hugh Trevor Roper, was declared persona non grata there. No future visitors by outsiders to BP were to be allowed unless sanctioned by Denniston.

With Russia an uneasy new ally and under great pressure following the Wehrmacht’s successful invasion, cipher security as well as the need to get vital information to the Russian High Command – Stalin – quickly, accurately and convincingly, was making slow progress but in September BP reported to Churchill that Hitler was about to turn his armies against Kiev; the outline of a Nazi plan to destroy three Soviet armies on the central eastern front, and that the German offensive against Moscow would begin on 2nd October.

In September BP’s other star mathematician, Gordon Welchman, reported to Travis his plan to upgrade and extend the remarkable successes of Hut 6. It had been decided that, in the event of an invasion of Britain, still in everyone’s minds as late as 1942, BP was to relocate to GHQ Home Forces and contingency plans were in place, though never tested. UK Sigint effort against the new ally Russia, the Soviet Union, was wound down and cipher cribs and clues exchanged with Moscow.

In the middle of October Churchill made his historic visit to BP. Later that month large scale building plans for BP’s new needs were developed. In November Dilly Knox and my father corresponded vitriolically but affectionately about the current management and Knox’s Enigma breakthrough. AGD reported on his trans-Atlantic visits, having deprived Herbert Yardley of his job running Canadian Sigint in Ottawa and re-established mutual confidence between BP and the American centre at Arlington.

On December 2 BP translated a second highly significant Japanese telegram from Bangkok to Tokyo, which reported that in order to ‘set up’ Britain as the aggressor against Thailand, elements in the Thai cabinet were suggesting that Japanese forces should land at Kota Bahru obliging the British forces in Malaya to invade from Padang Besar, whereupon Thailand would declare war on Britain.

The American codebreakers remained disgruntled to the very eve of war in December 1941. BP still refused to release the Enigma secrets to Washington. On Dec 5 the archives show, Commander Denniston nevertheless cabled to Captain Hastings (UK liaison chief) to Washington ‘I (AGD) still cannot understand what Noyes (US) wants’. With regard to Purple (US cipherbreak) he grumbled the British had already given the American codebreakers all they asked for, thus enabling them to ‘read all that we can read.’ AGD continued: ‘The main means of communication is ENIGMA. Twice, in Feb and July 1941, we captured keys for the month which we sent to Washington.’

BP noted: ‘I do not know if the American army cryptographers know that we are reading Japanese BJs’.

Denniston had confirmed the free exchange of all Axis intelligence during his August visit to the USA.

It was that summer of 1941 that the Americans sent a letter to BP asking for a cipher breaking machine. My father was aghast, as nothing was ever put on paper about ‘E’ - the Enigma secret. With a degree of frostiness in his reply AGD reminded the Americans that while ‘E’ was a matter of academic interest to them, it was a matter of life and death for the British… The Germans are always tightening up their cipher discipline and evolving new methods, and BP’s codebreakers felt they were “teetering on the edge of a precipice, they might be struck blind at any moment by a sudden German innovation”. The Washington visit talks would tackle the most sensitive subject namely the further exchange of codebreaking materials. At present, Denniston noted, this exchange is working very well but only on Jap - a ref. to the MAGICS.* Britain (noted AGD) could not transfer the Enigma secrets to the US, at most they might ship raw intercepts to Arlington and invite the US to try their hand at solving them. AGD hoped to set up a triangular liaison BP-Washington-Ottawa when he arrived on Aug l2, and ‘would then visit Ottawa, if this could be arranged without meeting Yardley’.**

Denniston was shaken by what he found in Washington. He visited the US’s radio monitoring station at Cheltenham, 30 miles from Washington but the country had nothing like GB’s own empire-wide Y radio-monitoring service. ‘It seemed incredible this feud between army and navy in USA, but this was what powerful vested interests involved had decreed.’ The US, my father reported, had done wonders with Magic but neglected JN (Japanese navy material). As a result of AGD’s visit the US naval codebreakers had only now undertaken to being collaborative with BP and the FECB in Singapore in investigating Jap naval cyphers and AGD stated they now regard this as one of their most important research jobs.

In my father’s report on his US trip 31/10/41 (HW 14/45), he said he found the Americans - apart from their magnificent work on MAGIC - scratching at the outside of the Italian, French and South American problems. He subsequently sent them all he knew about these as well as the French Colonial, Brazilian, Portuguese, Swedish and other ciphers GC&CS had penetrated.

Some of these enigmatic messages were taken by permission of the author from Churchill: Triumph in Adversity by David Irving. They confirm the importance Churchill and the British government attached to my father’s visit and its long-term influence on future US/UK co-operation in war and in peace.

* * *

IV

My father had written to Menzies, regarding his American visit:

1. Our American colleagues have been informed of the progress made on the Enigma machine.

2. They undertake to carry out their instruction to preserve the secrecy of this work and only their directors will be informed under a similar pledge.

3. Complete co-operation on every problem is now possible and we are drafting plans for its continuity.

4. As we cannot contemplate sending any senior member of our staff at present, it may be necessary to select some officer in our Embassy at Washington to act as our

liaison with their section. Perhaps you will nominate a suitable man.

5. As to telegraphic communications we have agreed to use the Anglo-American Naval Cipher with individual tables (OTP) which we are supplying (EWT). Our friends will arrange with their Embassy here for the receipt and dispatch of telegrams on their private cable. It will be necessary for us to arrange for a messenger to be available at Broadway to take or fetch telegrams on our behalf.

6. As to interchange of material, I presume we can use our diplomatic courrier (sic) service to Washington when the liaison officer referred to in para 4 has been nominated; they can no doubt use their courrier service and the bag can be collected by our messenger (mentioned in 5).

Denniston’s radical and innovative scheme for the free and complete exchange of cryptanalytical tools and product with the Americans was not followed up. This may well have to do with his increasingly painful genito-urinary condition. On 27 February, he had been diagnosed in Harley Street as having a stone in his bladder but had nonetheless managed to give lunch to the main US cryptanalysts, Rosen and Kullback at Stapleford Mill Farm where the Denniston family lived.

He was fully stretched with the increasing workload and amazing productivity of Bletchley Park. Work often kept him at BP by night as well as by day. Thereafter the removal of his stone and consequent painful orchitis kept him hors de combat.

Hindsight causes me to wonder whether at some point Menzies intervened and provided at government expense the medical and surgical care my father desperately needed. But he seems to have paid both hospital bills himself. His illhealth continued intermittently until his second American visit in September 1941 when his hosts, and in particular William Friedman, by now a good and trusted friend, had organised hospital treatment for him in New York, where the doctors employed a new irrigation technique which completely cured him. Of this visit one of the three leading American cryptanalysts wrote later: ‘that it laid the foundations for the collaboration between the cryptographic activities of the US and the UK which produced intelligence vital to the successful prosecution of World War Two. We spent considerable time together discussing the technical activities undertaken by both countries and worked out some of the details of our early collaborative efforts.’

* * *

V

My father shared with Churchill, Menzies and few others access to all Enigma messages (Ultra) of the German armed forces, as well as the diplomatic and commercial secret messages of the leading neutrals, particularly Turkey and Spain. The early months of 1941 were devoted by the British Foreign Office to attempts to pull Turkey into the war on the Allied side. It was in the end a failure, but Churchill pursued it unceasingly from 1941-3. Hitler had already overrun Poland, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and in early 1941 Jugoslavia, threatening Greece and Turkey. The brave Greeks resisted and joined the Allies while the Serbs added new strength to Axis activities in the Balkans. The British first sent the BEF (British Expeditionary Force, last seen at Dunkirk) to Greece, but pulled it out when it was clear there was no way Greece could be defended from the Nazis as well as Britain itself. The German invasion of Crete completed German superiority in the Eastern Mediterranean. All eyes then turned on Turkey.

For me, my first year as a scholar at Westminster in exile included a scout camp which ended on 16 August, when I returned to Stapleford Mill Farm. My father was far away. He had left on 10 August for the first and shorter of his two transatlantic visits. After a week at home with Y (our mother still worked at BP but was given compassionate hours to look after us) he was still away. We had no news of him. The Battle of the Atlantic was in full swing and we only knew that he had flown rather than gone by sea, as he had expected (‘Voyage’, he wrote tersely in his diary, later changed to ‘Flight’). BP were worried, my mother was worried, we were desperately worried. My dog Jaimie had walked into a ditch and died doing his bit to save rations. In fact my father was safely flown by Transport Command but many such planes were regularly shot down by the Luftwaffe. Crossing the Atlantic by sea was still more dangerous. By 8 pm on 23rd August we were reduced to sitting in the blackout, waiting and wondering. Perhaps my mother had some inkling that he was all right, but not certainly. There was a heart-stopping moment before we heard the crunch of car tyres on our farm track. Could it be? It was too much to hope. But it was.

It had taken him 15 hours flying from New York to Gander, Newfoundland, across the North Atlantic to Prestwick in the bomb rack and thence to Hendon where he was collected and driven home.

It was the best moment of all our lives. He had had an amazing week but he could not tell us anything about it. That did not matter. What mattered was that he was alive and okay. I relive that moment even today. Travis had cabled him on 8 August that ‘All well Soulbury 7’ (our telephone number) but we had no word from my father until his return.

* * *

VI

BP had had a successful war, and Whitehall by now was well aware of it. BP could write its own future as well, later, as record its own past. The result was two-fold. The future of GCHQ is a matter of record. It became a leading player in the Cold War, with huge investment in electronic surveillance, in alliance with NSA. But its future was a product of its past, building on the successes of Sigint interception, cryptanalysis and decryption on the work of BP.

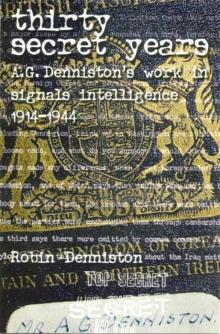

But this past extended back well beyond the war years of BP’s glory. It extended back to 1919 when the GC&CS was first set up and transferred from the Admiralty to the Foreign Office, and in fact to the autumn of 1914 when the interception of wireless messages passed between German ships to German High Command brought into being the vital cryptographic work of Room 40 OB. My father was one of the earliest recruits to Room 40, in 1914, became the Head of GC&CS in 1919 and remained so until February 1942.

He was thus the right person for senior staff at BP to have contacted when writing up its war work. But by 1944 there were few there who had any inkling of the importance of GC&CS prewar. Received wisdom by 1944 insisted that GC&CS was completely unprepared for war, failed to take on the mathematical needs of machine decipherment, run by amateurs unable to cope with Treasury mandarins, the needs of the armed forces or the requirements of BP’s enhanced wartime capability.

My father was quite aware of this. Though after February 1942 he seldom went to BP, he kept in touch with some old friends. It was in this context that he decided in late 1944 to offer his own account of GC&CS’s interwar years which began with a remark of Group Captain Sir Eric Jones, BP’s supremo after my father and Travis, about this period. ‘It would indeed be a tragic and retrograde step for intelligence as a whole and therefore…. for the future of the country if GC & CS were to slip from the record.’

In December 1944 my father wrote, and my mother typed, ‘The GC&CS between the wars’. It was circulated within the office and carefully studied by its recipients, comments were sent hither and thither between Whitehall and BP. They are all now in the National Archives. No criticism was made of any of the facts though there appears to have been no comment on the generosity with which he praised his colleagues.

My own reaction to it, after I read the comments, was to focus on critiques by his colleagues who also remembered the interwar years – in particular Josh Cooper and Nigel de Grey. Since I knew, having visited him shortly before his death, that Josh retained friendly memories of my father I was surprised at some of the apparently dismissive comments he made until I realised that he was addressing himself at this time to a group of BP leaders and historians who had fixed ideas about the inadequacies of GC&CS before 1940 in general and AGD in particular, so would not, perhaps could not, voice openly what he may have felt. So I referred the filed critiques to Sir Harry Hinsley, and asked in 1996 for his comments. In an undated reply on the back of college meeting minutes he had interesting remarks about the Cooper and de Grey’s critique:

‘Josh in Para 9 is right to stress that it was AGD who recruited the wartime staff from the universities with visits there

in 1937 and 1938 (also 1939 when he recruited me and 20 other undergraduates within two months of the outbreak of war). I believe this was a major contribution to the wartime successes – going to the right places and choosing the right people showed great foresight … There were many predators (the Services seriously thought of winding GC&CS down when the war came) and Josh would agree, I’m sure, that it was necessary to be diffident and understandable to be nervous. He quite rightly adds at the end of para 20 that AGD remembered WW1 very well but was tied by the narrow terms of reference imposed on him from above. This is an accurate conclusion.’

Of de Grey Hinsley wrote:

‘He says that more was achieved cryptographically before the war than is generally recognised, but that the over-all effort was limited by lack of funds as well as forgetfulness of the lessons about signals intelligence in war. But he added that the fault was not all or mainly the fault of GC&CS. “National policy was directed by axemen – very difficult to fight”.’

Of my father and Tiltman, Harry Hinsley wrote:

Thirty Secret Years

Thirty Secret Years